Part 2 of 2. (Photo: Scientists are homing in on how navigation skills develop. Credit: KNOWABLE MAGAZINE)

continuing from a previous article...

Mental mappers

That cascade presumably influences acquisition of the specific skills that are hallmarks of good navigators. These include the ability to estimate how far you’ve traveled, to read and remember maps (both printed and mental), to learn routes based on a sequence of landmarks and to understand where points are relative to one another.

Much of the research, though, has focused on two specific subskills: route-following by using landmarks — for example, turn left at the gas station, then go three blocks and turn right just past the red house — and what’s often termed “survey knowledge,” the ability to build and consult a mental map of a place.

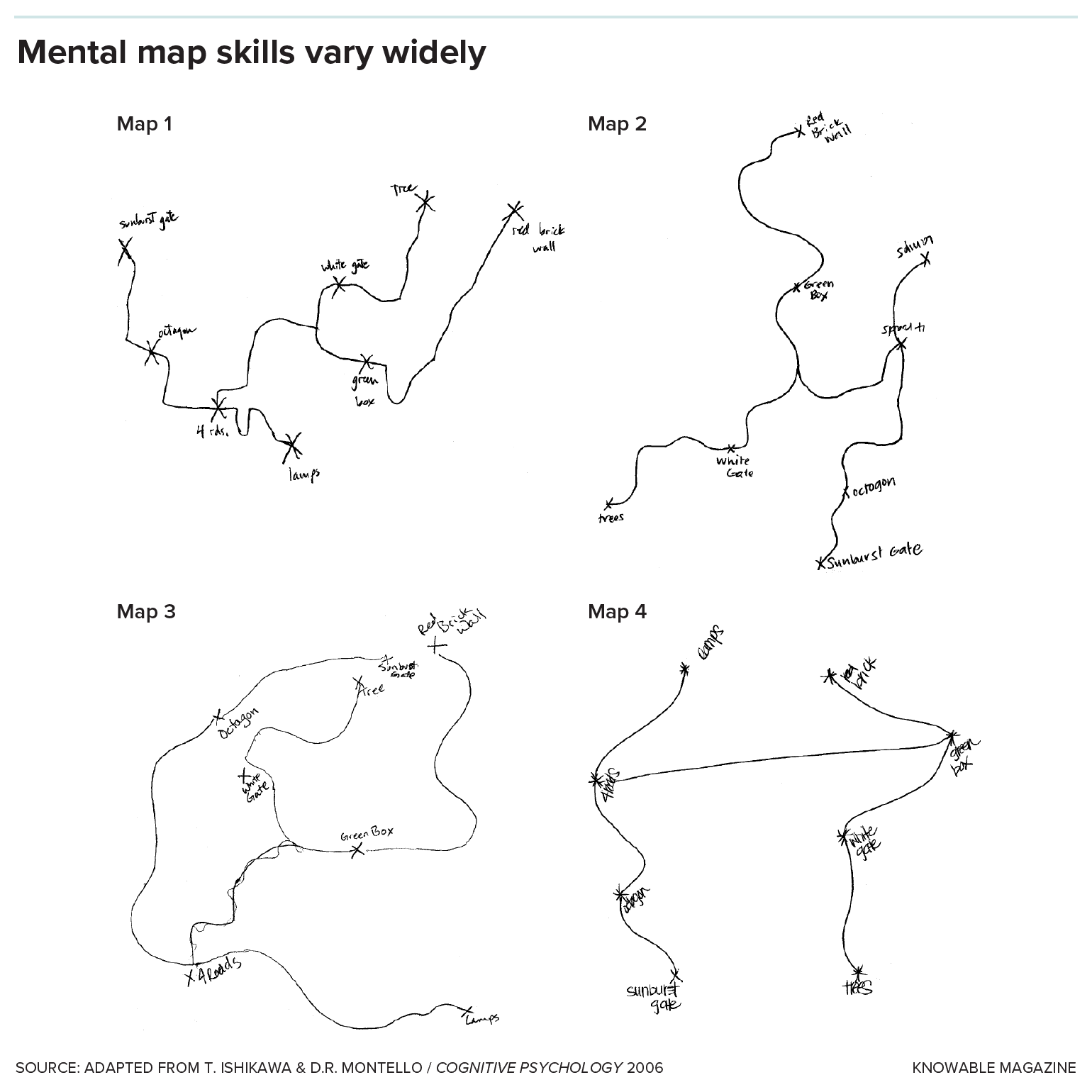

Of the two, route following is by far the easier task, and most people do pretty well at it once they’ve taken a route a few times, says Dan Montello, a geographer and psychologist also at UC Santa Barbara. In a classic experiment from almost two decades ago, Montello’s student Toru Ishikawa drove 24 volunteers, once a week for 10 weeks, on two twisting routes in a tony residential area of Santa Barbara that they’d never visited before.

Later, almost every person could accurately state the order of landmarks along each route and roughly estimate the distance travelled between them. But they varied widely in their ability to identify shortcuts between the two routes, point to landmarks not visible from where they stood, or sketch a map of the routes. Those who couldn’t identify shortcuts or find landmarks may suffer from an inability to create accurate mental maps, the researchers think.

Volunteers were driven repeatedly along two connected routes in an unfamiliar neighborhood and then asked to draw a map of the routes from memory. Their maps differed widely in quality, as these examples show. Map 1 (top left), from an excellent navigator, matches the actual routes almost perfectly; map 4 (bottom right), from a poor navigator, shows almost no correspondence to reality apart from the existence of two routes.

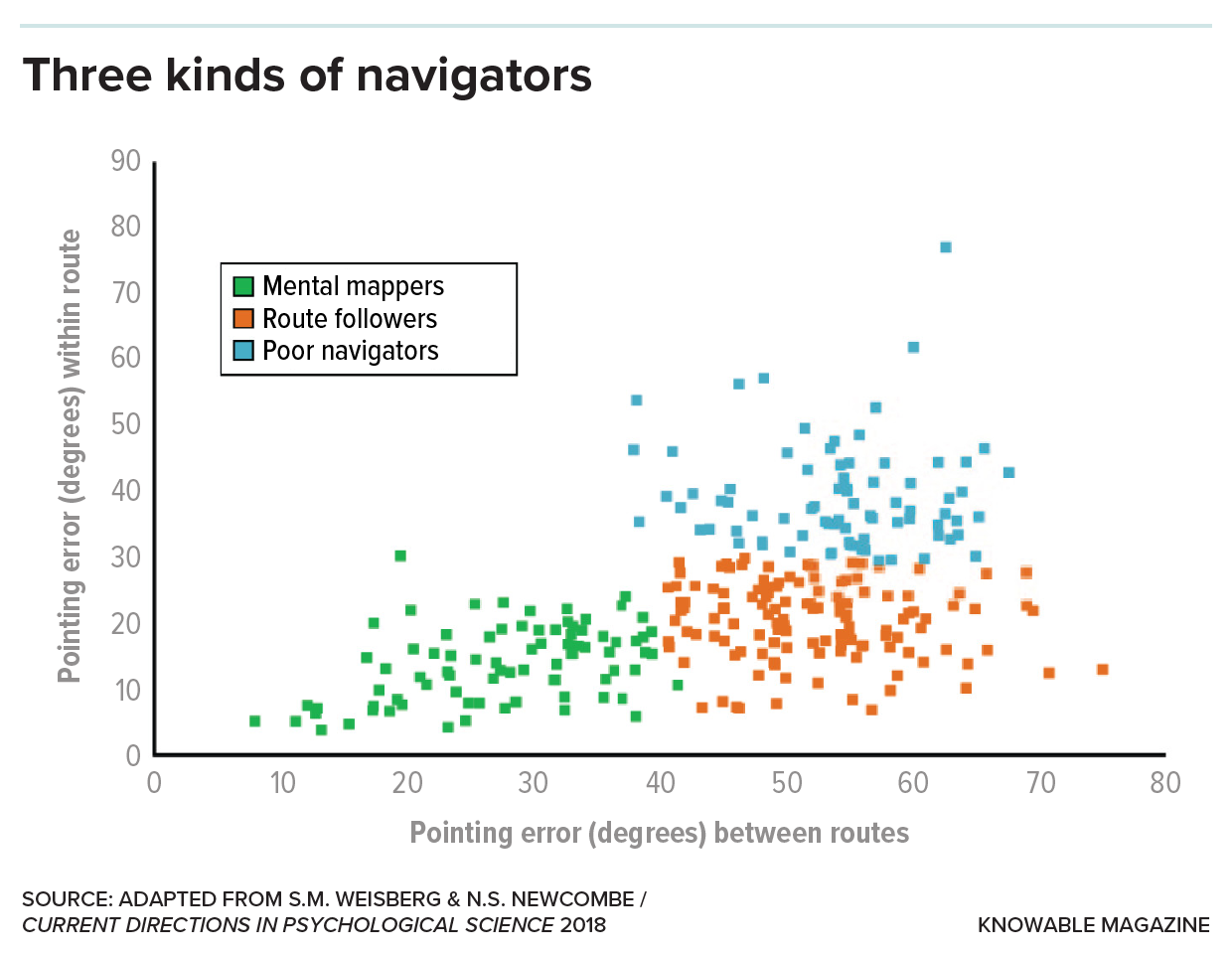

Research by Newcombe and her then graduate student Steven Weisberg underscores the importance of such mental maps in navigation. They asked 294 volunteers to use a mouse and computer screen to navigate along two routes through a virtual town. Once the volunteers had learned the routes and the landmarks they contained, the researchers asked them to stand at one landmark and point to others on both routes.

People fell into three classes, the researchers reported in 2018 in Current Directions in Psychological Science. Some people had formed a good mental map: They could point accurately to landmarks on both the same and different routes. Others had good route knowledge but struggled to create an integrated map: They were good at pointing within a route, but poor between routes. A third group was poor at all the pointing tasks.

That ability to build and refer to a mental map — a person’s survey knowledge — goes a long way toward explaining why they’re better navigators, Montello says. “When the only skill you have is the ability to think in terms of routes, you can’t be creative to get around barriers.” Survey knowledge gives the ability to navigate creatively, he says. “That’s a pretty stunning difference.”

Not surprisingly, better navigators may also be better at switching modes and choosing the most appropriate navigational strategy for the situation they find themselves in, says cognitive neuroscientist Weisberg, now at the University of Florida. This could mean using landmarks when they are obvious and mental maps when more sophisticated calculations are needed.

“I’ve moved toward thinking that our better navigators are also using a lot of alternate strategies,” Weisberg says. “And they’re doing so in a much more flexible way that affords different kinds of navigation, so that when they find themselves in a new situation, they’re better able to find their way."

Volunteers followed two routes in a virtual-reality urban setting and then were placed along one route and asked to point to out-of-sight landmarks on both the same route and the other route. Based on their accuracy in pointing (measured by how many degrees off the correct direction they were; 90 degrees is chance performance), researchers divided the volunteers into three groups: People with good mental maps (green), who pointed accurately both within and between routes; people with good route knowledge (orange), who pointed accurately within a route but not between routes; and people who were bad at both pointing tasks, indicating poor overall navigational ability (blue).

When Weisberg moves around Gainesville where he lives now, for example, he keeps track of north, because that works well in a city with a regular street grid; when he goes home to the winding streets of Philadelphia, he relies more on other cues to stay oriented.

Researchers do not yet know whether every bad navigator is simply poor at survey knowledge, or whether some of the lost might be failing at other navigational subskills instead, such as remembering landmarks or estimating distance traveled. Either way, what can poor navigators do to improve? That’s still an open question. “We all have our pet theories,” says Elizabeth Chrastil, a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of California, Irvine, “but they haven’t reached the level of testing yet.”

Pros and cons of GPS

Simply practicing seems like it should work — and, indeed, it does in lab experiments. “We can improve people’s navigational abilities in virtual environments,” says Arne Ekstrom, a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of Arizona. It takes about two weeks to show fairly dramatic gains — but it’s not yet clear whether people are really becoming better navigators or just getting better at finding their way through the particular virtual environments used in the experiments.

Support for the notion that people might improve with practice also comes from studies of what happens when people stop using their navigation skills. In a 2020 study published in Scientific Reports, for example, neuroscientists Louisa Dahmani and Véronique Bohbot of McGill University in Montreal recruited 50 young adults and questioned them about their lifetime experience of driving with GPS. Then they tested the volunteers in a virtual world that required them to navigate without GPS. The heaviest GPS users did worse, they found.

A follow-up with 13 of the volunteers three years later revealed that those who had used GPS the most during the intervening period experienced greater declines in their ability to navigate without GPS, strongly suggesting that GPS reliance causes diminished skills, rather than poor skills leading to greater GPS use.

Experts also suggest that struggling navigators like Uttal could try paying closer attention to compass directions or prominent landmarks as a way to integrate their movements into a mental map. For Weisberg, the only way he learns spaces in an integrated way is by paying attention to major cardinal directions or prominent landmarks like the ocean. “The more attention I pay, the better I can link things to the map in my head.” He recommends that struggling navigators ask themselves which way is north 10 times a day, referring to a map if necessary. This, he suggests, could help them move beyond mere route knowledge.

There’s another option for those who don’t really care about improving their skills as long as they just don’t get lost, Weisberg notes: Just make sure your GPS is handy.