(Photo: Renewable-energy milestones were met in 2025, with China being the first country to surpass 1 terawatt in installed solar-power capacity. Credit: Chen Kun/VCG via Getty)

The biggest science story this year was the political upheaval in the United States. Funding cuts, academic lay-offs and vaccine-sceptic policies have widely been seen as an attack on science, according to critics of President Donald Trump’s administration. The resulting damage to science could last way into the future.

But, there were also plenty of positive developments in 2025 that offer hope for the coming years. “From a non-US scientist, it’s somewhat business as usual. You just keep doing your job”, says Glen Peters, a climate-policy researcher at the Cicero Center for International Climate Research in Oslo.

Our recent Nature's 10 package includes many good news stories — and there were many more. From gene-editing firsts to rapid disease containment and policy victories, Nature takes a look at some positive science stories of 2025.

Species recovery

This year saw populations of some endangered and near-extinct species bounce back owing to strong conservation efforts.

The green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas), which has been endangered since the 1980s, has now moved to ‘least concern’ on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) red list. Efforts to protect the turtle’s eggs and measures to prevent their accidental capture in fishing nets have allowed populations to recover.

The ampurta (Dasycercus hillieri), a rat-sized Australian marsupial, moved from near-extinction to ‘least concern’ this year. Between 2015 and 2021, ampurta territory expanded by more than 48,000 square kilometres, despite dry conditions and food shortages.

Lastly, nations reached a historic milestone for marine conservation in September with the United Nations High Seas Treaty receiving approval from more than 60 countries. The treaty, which will come into effect in January, aims to legally protect biodiversity in international waters and conserve at least 30% of land and sea areas.

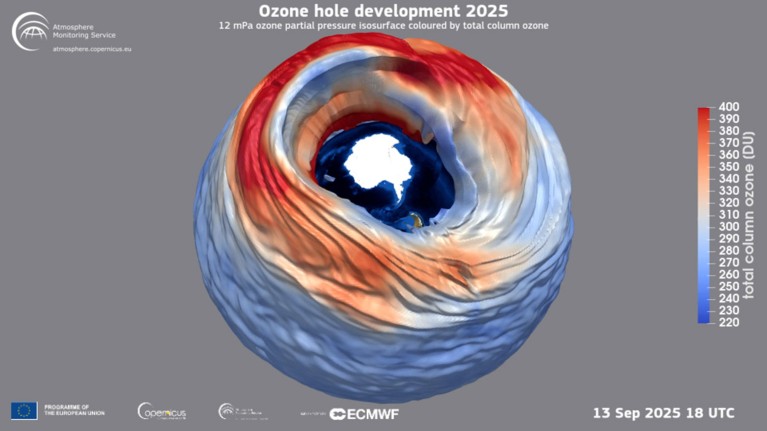

Ozone hole shrinks

The hole in the Antarctic ozone layer has shrunk to its smallest size since 2019, indicating the continued recovery of Earth’s protective upper atmosphere.

The ozone hole was first discovered in 1985 and is a result of human-emitted ozone-depleting chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), such as coolants in refrigerators and aerosol sprays. The Montreal Protocol in 1987 phased out the production and use of CFCs, which has successfully curbed emissions1 . Since 1987, the average size of the ozone hole throughout the year has been gradually decreasing in size, with the smallest so far in 2019.

The ozone hole is on track to recover completely in the late 2060s, provided efforts to find climate-friendly alternatives to CFCs continues.

The hole in the Antarctic ozone layer has continued to shrink.Credit: CAMS

Gene-editing successes

This year “was a breakthrough year for gene editing,” says David Liu, a chemical biologist at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard in Cambridge, Massachusetts. “In 2025, these technologies have achieved a number of medical milestones.”

“I view this year as an outstanding one, marked by the launch of many clinical trials”, adds Annarita Miccio, who studies gene therapy at the Imagine Institute at the Necker Hospital for Sick Children in Paris.

The first gene therapy for Huntington’s disease proved striking, slowing the rate of cognitive decline in participants by 75%. Another gene-therapy trial for T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia showed promise with the majority of 11 participating children and adults entering remission2. The new type of CAR-T-cell therapy uses base-editing technology to modify several genes in T cells, helping them to target the cancer cells.

Researchers also trialled the first use of a CRISPR technology tailored to an individual this year. Other successes include the first clinical trial for a gene therapy to treat a rare immune disorder called chronic granulomatous disease3, and another that corrected a pathogenic mutation, which can cause lung damage and liver disease4.

These clinical trials paved the way for developing mutation-specific strategies for rare diseases and demonstrated that collaboration between academia and industry can lead to cures for people with such diseases, says Miccio.

Renewable-energy boost

Renewable energy surpassed coal as the largest energy source for the first time globally this year. The achievement was helped by China becoming the first country in the world to install 1 terawatt of solar power capacity in May. In the first six months of 2025 alone, China installed new solar systems with a capacity of 256 gigawatts — twice as much as the rest of the world combined. The country plans to add a further 200–300 gigawatts of capacity for solar and wind energy in its five year plan, beginning in 2026.

“China and many developing countries are deploying solar and wind [and] electric vehicles at pretty breakneck pace,” says Peters.

Around half of the European Union’s demand for electricity came from from renewables in the second and third quarters of this year. Renewable-energy capacity is projected to increase by almost 4,600 gigawatts between 2025 and 2030 — double the capacity deployed between 2019 and 2024.

However, greenhouse-gas emissions from fossil fuels reached a new high this year. It remains to be seen whether renewable energy can replace fossil fuels as the dominant global energy sources.

Ebola contained

In September, heroic efforts from health workers and African governments contained an outbreak of Ebola in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) in just 42 days. On 4 September the outbreak in the Kasai province was confirmed by the Ministry of Health to be Zaire ebolavirus. In total, 64 cases were reported, with the last case reported on 25 September.

A rapid response from local health services in the Democratic Republic of the Congo successfully curbed an outbreak of Ebola in the Kasai province.Credit: Xinhua/Shutterstock

Although the remoteness of these areas made it difficult for responders to gain access, it also helped to prevent the spread of the virus, says Henry Kyobe Bosa, who leads the Ebola and COVID-19 response for Uganda’s Ministry of Health.

Vaccine roll-out and treatment with a monoclonal antibody therapy both began soon after the outbreak was declared, which helped to prevent serious illness. “We are improving in the management, the response, the community engagement and the contact tracing”, says Bosa.

New malaria drugs

In November, the World Health Organization (WHO) approved the first malaria treatment for infants. Given that, currently, children under the age of five account for around 75% of malaria deaths globally, the medicine could bring the world one step closer to eliminating the disease.

An infant version of the treatment, called Coartem (artemether–lumefantrine), “provides a drug formulation that can now be safely used to treat malaria in the relatively neglected population of babies and young infants”, says Jane Achan, a paediatrician who specializes in infectious diseases and principal adviser at the Malaria Consortium in London. “It most definitely will have wide implications especially in improving treatment of malaria in the populations at risk, and also improving treatment outcomes among babies and young infants and in settings with drug-resistant malaria parasites”, she adds.

In a phase III clinical trial this year, a second malaria drug called ganaplacide–lumefantrine (GanLum) successfully treated malaria in 97.4% of participants. GanLum also cleared parasites that have developed resistance to the antimalarial drug artemisinin.

If GanLum receives regulatory approval, it will be the first new class of malaria medicine in more than 25 years.

Peanut allergies plummet

A study showed that peanut allergies in children have fallen in the United States in the last decade, in a major victory for science-based policy and decision-making5 . For years, parents were told not to expose their babies to peanuts to prevent dangerous allergic reactions. But a landmark study6 in 2015 found the opposite to be true — when infants are introduced to peanut products as early as four months old, they are much less likely to become allergic to them. The study led to a change in health guidelines between 2015 and 2017.

Now, there has been a 43% decrease in peanut allergy prevalence in children under three in the United States, compared with 2012. The same method of exposing infants to a variety of other allergens also led to a 36% reduction in other food allergies. “This is a good year to have a peanut allergy or a food allergy,” says Michael Pistiner, a paediatric allergist at Mass General Brigham for Children in Boston, Massachusetts. “So much of our field has been witnessing changes for the better, this particular year has been exciting.”

“This is a great example of translating controlled trial findings into broader community level outcomes,” Pistiner says.