13 mins read//

Today, James Dyson is a billionaire who runs a family-owned empire of vacuums, air purifiers, and other high-tech, high-design remakes of otherwise humble appliances. But that success was in no way obvious. As a young inventor and entrepreneur, he stumbled his way through several startups, learning to succeed in his own way, all while stacking up tremendous personal debt.

It wasn’t until age 48—following a decade of development on his vacuum—that Dyson finally paid off his personal loans, which had escalated to the equivalent of $900,000. The rest is history.

Dyson details this story of his life (and its many inventions) in his new memoir, Invention: A Life, which is available now. To mark the book’s release, I sat down for an hour with Dyson, in what turned out to be a frank, and often self-effacing, interview.

I asked him to deconstruct some of the most defining moments of his career. Here’s an abridged story of his life, through his inventions.

[Photo: courtesy Dyson]

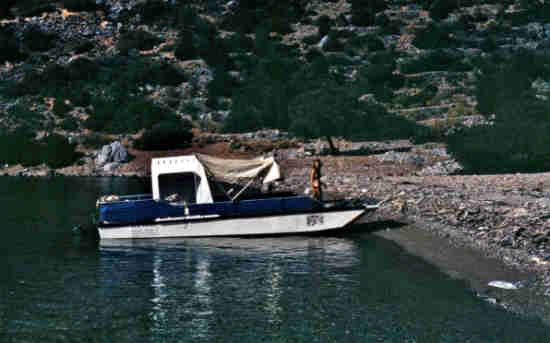

THE SEA TRUCK

As a third year student at the Royal College of Art, Dyson designed a Buckminster Fuller-inspired children’s theater, shaped something like a tree house or giant mushroom. To fund the creation, Dyson met Jeremy Fry, a famous British engineer who ran the engineering company Rotork.

Fry wouldn’t fund Dyson’s theater. But he would become Dyson’s biggest mentor and champion. While Dyson was still a student, Fry offered him a job—to found the marine division of his company and build an object that had only been floating in Fry’s imagination: The Sea Truck, a fiberglass truck that could drive into the water, then operate like a boat.

Dyson built the boat. But then he was tasked with traveling around the world to sell it.

Fast Company: So I think the place to start would be the Sea Truck.

James Dyson: It was a revolutionary type of boat, which no one was interested in at first because no one really believed it. Someone described it as looking like “a Welsh dresser on water.” So there was a huge resistance to it, and reaching your customer is quite difficult, because you just don’t know who needs to buy a boat. Because obviously it wasn’t consumers, apart from one or two Scottish lads who owned islands, so you don’t know who your customer’s going to be.

[Photo: courtesy Dyson]

So cold calling is hopeless, apart from obviously armies and navies who you can approach. But otherwise you just have to wait for people to approach you. So getting acceptance of this Welsh dresser on water was difficult. I wouldn’t claim to be particularly good at that, the whole business of marketing, of creating desire, writing brochures—as they were in those days, we don’t do them now, but we do an equivalent, a webpage or whatever.

And [yet] I really enjoyed it. Learning all that was wonderful. I flew all over the world, and I was selling to the Peruvians, the Venezuelans, the Malaysians. It was really interesting, but it got to the point where . . . I mean, the arms trade at that time, in the early ’70s, was not quite the place you wanted to be.

FC: I’m not so sure the arms trade is where you want to be today, either.

JD: I learned about making things, I learned about selling things, I learned about managing a business. I just felt it wasn’t really for me, that sort of business; I wanted to design things for ordinary people.

FC: So you recognized your nature from an early stage, in that regard?

JD: No, no. I think I learned it through talking to [Jeremy Fry]. Being around a charismatic entrepreneur, he and I had lots of discussions about some of our heroes, like André Citroën, and how did they do it? How did they develop things and produce products and make them successful? Those sort of conversations made me want to be an André Citroën or a [Soichiro] Honda.

[Photo: courtesy Dyson]

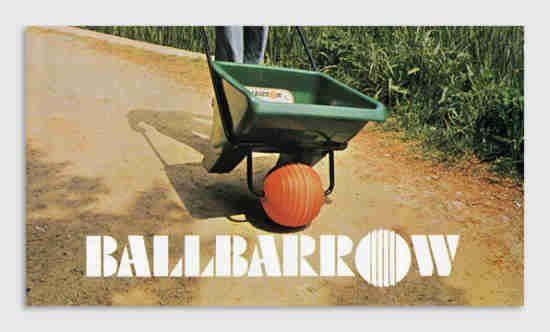

THE BALLBARROW

Drawn to humble objects, with a more obvious market, Dyson leveraged his own love for gardening into his next venture: The Ballbarrow. It was a wheelbarrow that replaced the front tire with a bright red ball and was easier to roll on unsteady surfaces. Dyson went all-in with this invention, which was as ordinary as inventions get. He designed it and even manufactured it himself.

The Ballbarrow was an award-winning product that would spawn variations and spinoffs. But it still wasn’t a sustainable commercial success for Dyson, as the Ballbarrow was built upon a business plan that was doomed from the start. Dyson turned down Fry’s offer to fund the venture and opted to take a high-interest loan from a bank instead, an error he considers one of the largest he’s ever made, eventually leading Dyson to lose rights to his own invention. Dyson would also learn important lessons on not just building a product, but building a product you could make money on.

[Photo: courtesy Dyson]

FC: So you spun off from Fry with the Ballbarrow.

JD: Yes, I wanted to do it on my own, rather stupidly actually, because he said he would back it, and very stupidly I turned him down because I wanted a complete break. But in fact, he understood me, he understands the problems of developing products and putting them into production, and he would’ve been a much better investor than the investors I ultimately chose to have. So that was an important lesson, if you choose an investor—if you have to have an investor—choose one who understands you and understands what you’re doing, and knows something about it and can be a help. A mentor maybe, but who understands what they’re getting into when they put the money in.

FC: But here’s what I’ve never understood: The Ballbarrow won an award from the British Design Council. It is still a great idea. I’d buy this today! Why did it go under?

[Photo: courtesy Dyson]

JD: I didn’t know how to do market research. And it was a very difficult market to reach in those days. There weren’t chains of garden centers, and there weren’t even chains of hardware shops like Lowe’s or Home Depot. Those didn’t exist. So you had [to distribute through] wholesalers selling to the retailers. We had to go around to the individual hardware stores and the individual garden centers, and try and sell them one Ballbarrow or two Ballbarrows, right? And then we’d gather those orders up and go to the wholesaler and say, ‘Here you are, we’ve got orders from 10 of your retailers for 50 Ballbarrows, will you give us an order for 50 Ballbarrows?’ And we were giving all the profit away to the wholesaler, and of course the retailer, and it was very hard work, whereas our competitors usually had a whole stable of products, and that made it much more sensible. [Their] salesman could take orders for sprayers, for strawberry growers, for flower pots, whatever else it was, and so it made the salesman’s visit worthwhile.

So know your method of distribution, was the lesson I learned, and don’t do a seasonal product.

FC: These days, direct-to-consumer products are a huge business, and a business Dyson is in, for just that reason of distribution! But is selling seasonal products really that difficult?

JD: Absolutely awful. It’s really awful because, well, in the wheelbarrow case, your only demand is in the summer and the spring. And so you’ve got to keep the workforce going for the rest of the year, you’ve got to build up stocks, and you have cash flow issues; and then you get a bad summer and you’re stuffed [with inventory], or a late start to the summer, curiously. I thought if you had a late start to the summer, at least you’d catch up, but you don’t.

[Photo: courtesy Dyson]

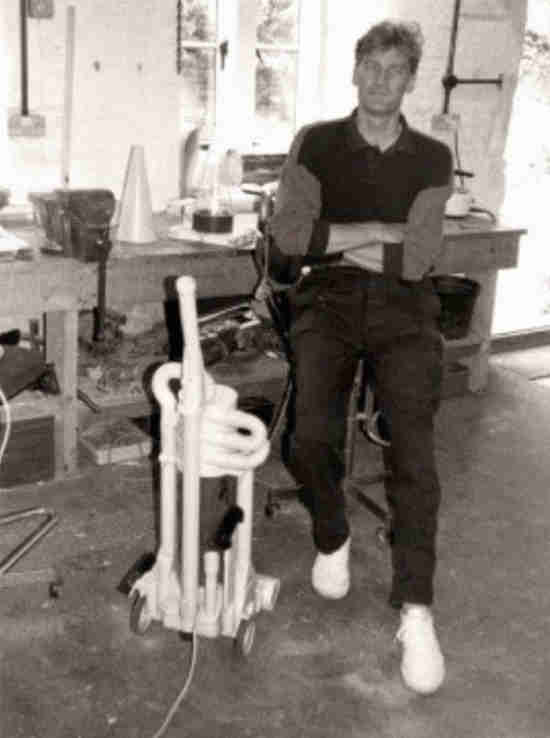

THE VACUUM

The Ballbarrow left Dyson with less than nothing: He was in considerable debt. But while producing the Ballbarrow, he’d come up with another idea. The Ballbarrow factory was constantly full of an epoxy powder that was sprayed on the Ballbarrow frames. To clear the air, Dyson’s factory used a giant fan, which got clogged on a daily basis. He learned that other factories used giant cyclones to do the same job, which used centrifugal force to collect dust instead of filters.

In the middle of the night, Dyson snuck into a local timber factory with a flashlight and notebook to study its cyclone. Dyson cloned his own 32-foot cyclone for the Ballbarrow factory. But he began to wonder why vacuums didn’t do the same thing.

In 1979, after giving up on the Ballbarrow, Dyson sat in his garage and made his first miniature cyclone out of mere cardboard—this one measured less than a foot in length. After a promising test, Dyson enlisted Fry for some seed capital. Then he went into his carriage house and built 5,127 variations—carefully accounting for one single small variable at a time—until he finally developed one that could trap tiny particles.

Fry and Dyson had decided to never build their own vacuum and license the technology instead. Ten years passed in which Dyson resisted manufacturing his own vacuum cleaner, so scarred by the Ballbarrow experience. But most of the world’s leading vacuum manufacturers refused to license Dyson’s vacuum technology. Notably, Amway backed out of a licensing agreement with Dyson, but then cloned the cyclone technology itself. Dyson ended up in a five-year legal battle with Amway over this, which he’d win, but Fry would leave the company after. This left Dyson back at square one.

FC: You said you’d never manufacture anything again after the Ballbarrow. That was the lesson! But then . . . you decided to manufacture a vacuum cleaner.

JD: We settled and got a big payment on the [vacuum] lawsuit, and I got rid of the cost of the lawsuit. It was at that point that I said, “Look, I know I didn’t want to be a manufacturer again, but I’ve really got to be a manufacturer again. I can’t go on with this wretched business of trying to license people and having them give up on the agreements, and legal issues the whole time. Frankly, it’s easier to make things, and I can’t go on with it not being a success, I can’t take it any longer.” And by then, I’d got just three wonderful young engineers working with me, and we thought we could make a go of it.

[Photo: courtesy Dyson]

FC: It’s interesting to me, because it feels obvious in retrospect because it worked out, but when I read through the actual story and hear you tell the story, it feels like what you learned from the Ballbarrow was like, “Don’t do all that work yourself, that’s crazy. You take on all this risk building this, you have inventory, you have all these problems.” And then with a far more complicated machine, you said, “Oh, we’re going to make it ourselves.”

JD: Well, actually I think it turned out to be a lot quicker, a lot happier, and a lot more successful than trying to license and get other people to make it. I mean, I’d spent 10 years trying to license other people and it not working, and my patents were running out, the patents would totally expire. And also, what I’d learned, is that going around [in attempts to license the cyclone to] these, the Hoovers, Electrolux, Mieles, Boschs of this world . . . each one of them turned it down without a good reason. . . . So curiously, that failure and the rejection by all those manufacturers in every country gave me the impetus to do it myself.

Yes. It was a volte-face, but it was a volte-face born of frustration; and suddenly, the knowledge that these guys are not interested in doing anything new. And it’s not a seasonal product, every home needs at least one, hopefully more than one. And you can ship them internationally, which you couldn’t do with a Ballbarrow, they take too much room in a container, and they’re not of high enough value.

FC: But you had to manufacture again!

JD: Yes, OK, I had to get back into manufacturing, to the onerous and troublesome business of manufacturing; but actually, I’ve quite enjoyed it. It was not easy, and it’s not easy now, by the way. I mean, during COVID, it’s been extremely difficult because factories have been closed, so it’s not easy, but it’s a lot easier than trying to license people; you’re sort of in control.

FC: When I was reading the book, I felt like the takeaway of the vacuum—and a lot of Dyson’s ongoing inventions up to the car—was, if there’s something critical, you need to make it yourself.

JD: [Since getting into manufacturing], it’s been a constant [challenge where we] couldn’t get enough plastic molding, so we started doing plastic molding in-house. Now we make our electric motors, we’re going to make our own batteries, we’re making our own heaters. So if we got a bit of real breakthrough technology, we make it ourselves; because in the making of it, you learn how to make it even better and develop it even better, which is why we did the [vacuum and car] motors ourselves.

FC: Is there a rule of thumb you can at least see in retrospect about when it was right to invest in your own tech and to own that entirely, versus when it was worth sourcing apart from the third-party manufacturer and leaving that piece of the pie for them?

JD: Yes. We were sourcing electric motors from electric motor manufacturers and we could see they weren’t making any progress, they weren’t changing it, and I’d had this dream for quite a long time of making ultra high-speed electric motors so they could be much smaller and lighter. And quite a long time ago, I approached a motor manufacturer, but I realized they didn’t want to take that kind of risk and that kind of investment if they didn’t have a customer for it, because they’re not in that sort of business. They make things for people who want that thing, they’re not risk-takers themselves. So I knew we’d have to do it ourselves, so I had to start from scratch. I had to recruit a team of people from universities, who were doing new technology with electric motors, and we started doing what we wanted to do, and we built up that team. And it’s been the same with robotics, it’s been the same with the heater, and the same with our batteries. And of course, it takes much longer than you ever think.

[Photo: courtesy Dyson]

FC: Right. I feel like that’s a superpower you’ve had, that steadfastness. I don’t know that I could be in debt for so much of my life and just rely on my own breakthrough in that regard, or my own guile in terms of winning people over to an idea.

JD: Yeah, but you get involved! It’s difficult to explain that to people who haven’t been in manufacturing or engineering, but you get drawn in and involved and you can’t let it go; it gnaws away at you and you’ve got to beat it. Yeah, OK, maybe you need a bit of determination, a bit of stamina, but it’s enjoyable. I mean, not that you’re smiling all the time, but I mean, it’s absolutely absorbing.

FC: I think this probably brings us to the car.

[Photo: courtesy Dyson]

THE (UNRELEASED) DYSON CAR

After the vacuum, Dyson the company went on to release numerous hit products. But Dyson the man had long been obsessed with building a zero-emissions car. With motor and battery technology so core to the company’s products, an electric car was in some sense a next, logical step.

But after years of work, and having built a functional prototype—more of which is detailed in the book chapter here—Dyson shuttered the car project, after hundreds of millions of dollars in losses to his company.

[Photo: courtesy Dyson]

FC: What did you learn from the car?

JD: I mean, we didn’t learn an awful lot that was helpful with everything else we’re doing, because the car business is so different, and car engineering is so different. The greatest thing we got from it was some more wonderful engineers who’ve come into our existing business. And I think in the long term, 500 million pounds wasted on the car project, in the long term we’ll get it back through that injection of talent.

[Photo: courtesy Dyson]

But I can’t say we’d learned an awful lot. We got into a lot of new areas like aerodynamics and suspension, tires, and lots of interesting things, and maybe little bits of it will pop up in things that we’re doing. But there’s no big thing that helps us, in that sense it was a real dead end. I mean, it’s all fascinating, and we loved doing it, but I’m not sure that we got a lot from it.

[Photo: courtesy Dyson]

FC: I’ve talked to a lot about entrepreneurs who’ve had various businesses fail over the years, and the one takeaway to me is that they are still glad they went for it. I’ve never heard anybody regret it. Can you look at the car like that?

JD: Not really.

FC: Seriously?

JD: Not really, not really. I mean, because a huge amount of time went into it, four or five years, a huge amount of time and effort. And I enjoyed it, so we got enjoyment out of it, but it didn’t really advance us. If we had shareholders’ funds, we could’ve probably battled through knowing that we had our battery technology coming along, and we already designed a range of cars based on that chassis. So I think we could have turned it into a successful business in the end, but as a private company, it would’ve hamstrung us for a long time.

[Photo: courtesy Dyson]

THE FARM

Today, James Dyson is the largest landowner in England. And he’s dedicating this real estate to farming. The business is not profitable for Dyson—and contrary to some claims, Dyson insists he’s receiving no federal subsidies for running the farms. Instead, it’s a passion project, and a meaningful topic that he’d like to contribute toward global health and stability.

FC: Why get into farming? You’re a technologist!

JD: I wanted to do it because I grew up on farms; I didn’t own a farm, but I worked on them in a heavily agricultural area, a rather beautiful agricultural area. So I wanted to do it because I saw it as another form of manufacturing, and it’s a wonderful thing to do, to produce food. It feeds the nation, it’s an important thing to do, so that’s why I did it.

FC: Is farming a viable business for you? So much of farming here the U.S. isn’t really profitable, it’s government subsidized, much like in Europe.

JD: Of course, I’ve learned that you can’t make money out of it—growing peas, it’s impossible to make money growing peas. We are making a tiny bit of money out of strawberries, growing strawberries out of season. But it’s interesting, because [subsidies create] huge pressure on what you do, and you’ve got to innovate and work a way through it. And also one other big issue is, it’s a bit like the early days of the Ballbarrow, the problem is that everybody else is making money except the farmer, because wholesalers are making money, and of course the supermarkets are making money, but we’re not.

[Photo: courtesy Dyson]

FC: Right, a retailer is marking up your product.

JD: I mean, there are 250,000 farmers in England and four [chain] supermarkets, so the boot’s on the wrong foot, you see? And the supermarkets try to pretend it’s their food, and it isn’t their food. They’re not the growers of it, they’re merely the warehouse for it. Anyway, I think we’ll get there, and I think people are starting to care about where the food comes from and how it’s grown and who’s growing it. I think food is our most basic need, and I think growing food is incredibly important, and working out how to do it more directly and more profitably will be an interesting conundrum.

[Photo: courtesy Dyson]

FC: I have a few garden boxes in my backyard, and there’s nothing quite like growing food. My grandpa was a farmer; I never knew him, but I can imagine that feeling only scales when you get the incredible automation and things we have today, and you build in all the hyper-efficiencies of modern science.

JD: And it’s just wonderful seeing the harvesting machines going, and the pea vining; you have these peas and we have this harvester which goes along, it takes in the whole plant and shells the peas and puts them in a hopper, which it can then feed to a combine; a trailer going next to it, it chucks the chopped up plant back on the ground. The next day we come along and plant cabbages in the field. There’s this mess of peas there, you don’t turn the ground or anything, you just put the cabbage in, and the peas rot and provide compost and fertilizer for the cabbage. And when you see this on a very large scale, it’s, well, “awesome” is a good word to describe it.

Source: https://www.fastcompany.com/90681619/from-nearly-1-million-in-debt-to-a-household-name-james-dyson-dishes-on-his-biggest-hits-and-misses